Solar sanitation solutions (Day 343)

5th May 2015

Poor sanitation results in contaminated drinking water and the spread of infectious diseases including Cholera and Dysentery, which cause severe diarrhoea, dehydration and if left untreated, death (see my blog, 'Everyone should have a human right to water').

Every year, around 1.5 million people - mostly children under five years old - die from diarrhoea. Drastic action is needed in order to make safe sanitation accessible to all.

Only last week, I observed that we sometimes have a tendency to take things for granted in the developed world. My blog, ‘Chemical engineer develops sanitary towels to help girls stay in school’ was well received and has prompted me to look at some other work by chemical engineers who are making a difference in the developing world.

Four years ago, in a bid to tackle polluted water and poor sanitation, the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation established ‘Reinventing the Toilet Challenge’.

Now although I've blogged about toilets before (See ‘Chemical engineers on the toilet’, and ‘No waste for music lovers’), this is a crucial issue and one where chemical engineering can play a major role; so today I'm highlighting the Solar Toilet, which won first place in the inaugural Toilet Challenge.

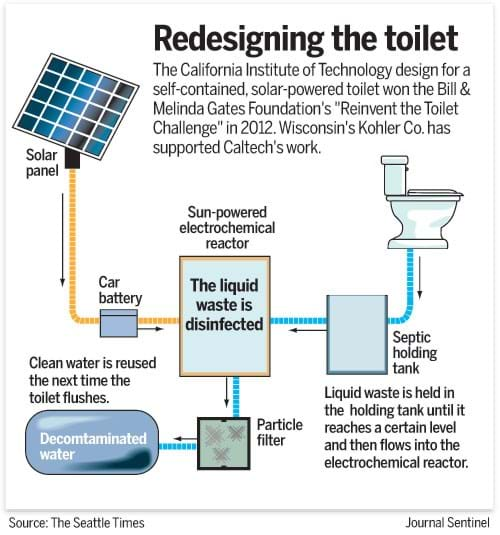

A team from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), US, led by Professor of Environmental Science, Michael Hoffmann, designed and built a self-contained solar and fuel cell-powered toilet.

The toilet is completely self-contained and does not need to be hooked up to any sewer or power systems, nor does it pollute the immediate environment. It also produces hydrogen, which can be diverted to a fuel cell that can power the toilet at night, and fertilizer as by-products.

It is also cost-effective. Costing about five cents per user, per day.

After an initial flush, waste treatment starts in a septic holding tank. Sedimentation occurs, and anaerobic digestion by bacteria.

The supernatant liquid above the sediment passes to an electrochemical reactor, designed and constructed by Michael’s team. The waste is oxidised at a semiconductor anode, whilst water is reduced at a metal cathode to produce hydrogen. The electrical power needed to drive the electrochemical reaction comes from a car battery that is recharged from solar panels on the toilet roof.

The process also uses sodium chloride (from common salt). The chloride ions are oxidised to a reactive chlorine species, which increases the effectiveness of the disinfection and waste treatment.

After going through a four-hour treatment cycle, the clean water can either be filtered and reused to flush the toilet, or for local crop irrigation. The residual sediment in the septic holding tank can be removed and used as fertiliser.

This YouTube video explaining how the toilet works:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVQaMsvBLb8

In February 2014, one unit was installed in the city of Ahmedabad in the Gujarat, India. Clèment Cid, a Caltech graduate in Environmental Science and Engineering who worked on the project, said the system would cost around £1,000 to install and has a lifetime of 20 years. Development work is continuing.

I agree with the view expressed by the former UN secretary-general , Kofi Annan, who said, "Access to safe water is a fundamental human need and therefore a basic human right."

Chemical engineering is part of the solution. That's why chemical engineering matters. Chemical engineers adopt a solution-based approach to design, build, operate and manage safe and sustainable processes that deliver products and services which people need.

I look forward to seeing further life changing inventions emerge from the ‘Reinventing the Toilet Challenge’.

Are you involved in finding chemically engineered solutions to developing world challenges? Click here to get in touch and tell us about your work.