Smarter Teflon recycling in South Africa (Day 293)

16th March 2015

Fluorspar, or fluorite, is the mineral form of calcium fluoride and the key raw material in the production of hydrofluoric acid, a significant commodity chemical with a wide rage of uses. South Africa is a producer of acid grade-fluorspar, but around 95 per cent of its production is exported.

However, heavy reliance on income from the export of low value materials can hamper a nation's economic prospects and render it vulnerable to global price fluctuations.

An initiative from the Southern African Department of Trade and Industry aims to address this challenge via a two-pronged approach. First, by developing cutting-edge technology in fluorochemicals and also by accelerating the skills development in fluorine engineering through world class research.

Chemical engineers working in the Department of Chemical Engineering at University of Pretoria, South Africa, have focused their work on the production of novel fluoro-materials, development of dry-fluorination reactions and modification of polymer properties by reactive processing.

Their research also involves chemical engineers from the University of KwaZulu-Natal and an industry consortium.

The Institute of Applied Materials at the University of Pretoria is building on this fluoro-chemical research, with Professor Philip Crouse, who holds the position of Research Chair in fluoro-materials science and process integration, in the lead.

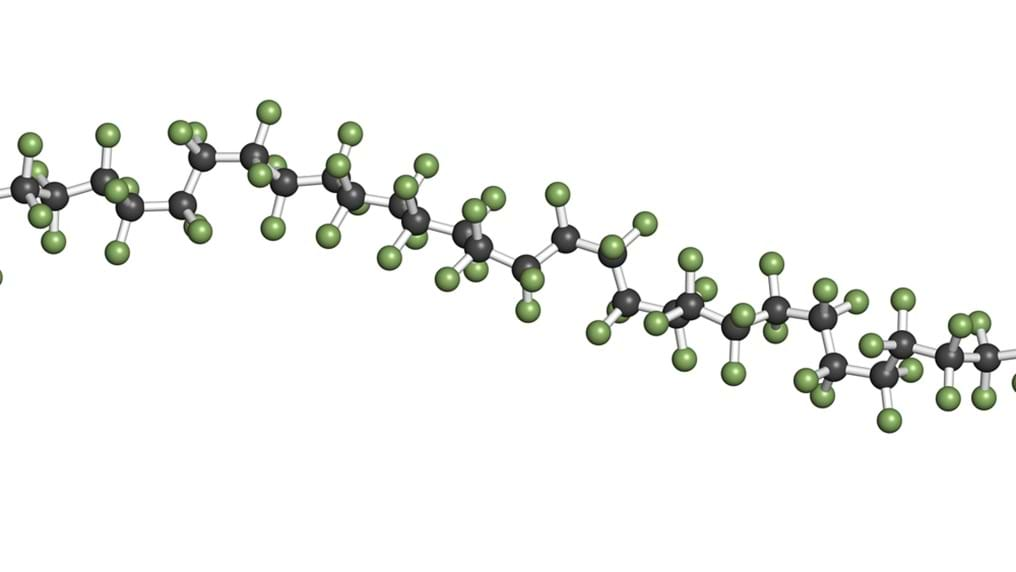

Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) - better known as Teflon® is probably the most recognisable flouorous material.

In 2012, global PTFE demand was estimated at 248,000 tonnes with sales totalling US$ 3.4 billion.

The use of fluoro-chemicals is widespread, with many applications, from corrosion inhibitors for plastic film packaging materials, flame retardants and non-stick coatings.

Suspension polymerisation is used to produce high molecular weight PTFE. The unique properties of the polymer are what make it so useful, but its resistance to fairly high temperatures mean it cannot be moulded by heating or melting. It must be compressed.

Philip's research includes investigating the effect of metal sulfates and fluorides and metal oxides on the catalysed pyrolysis (thermal decomposition) of PTFE.

To breakdown and recycle PTFE you need temperatures of over 500°C, which produces a mixture of smaller molecules. Some of these molecules are valuable and useful in other applications e.g. hexafluoroethane (HFE), which is used in the manufacture of semiconductors.

Philip has been working on accelerating the rate of degradation of PTFE by using a variety of catalysts including: copper(II) sulfate; aluminium fluoride; vanadium(V) oxide and copper(II) oxide.

The use of copper(II) sulfate, aluminium fluoride and vanadium(V) oxide reduced the temperature at which decomposition started by 30-50ºC. Whereas aluminium sulfate, nickel sulfate and aluminium oxide all promoted greater selectivity for the production of HFE. Both findings offer significant advantages.

Philip and his team have demonstrated that aluminium fluoride, aluminium sulfate and nickel sulfate are all potential catalysts for PTFE pyrolysis. This enhanced understanding of the decomposition of PTFE will also aid development of a process to recover valuable products from its waste streams.

Philip and his team are advancing our understanding of the processing of fluoro material's. It's always good to hear about research that is focused on developing competence and accelerating economic growth and I wish them every success in their work.