The Complexities of Carbon Capture and Storage (Day 238)

20th January 2015

Some of the best work being done in carbon capture and storage (CCS) is helping us to question whether the assumptions we make are correct.

Research from the Department of Chemical Engineering and Biotechnology at the University of Cambridge suggests that natural geochemical reactions can delay or even prevent the spreading of carbon dioxide (CO2) in subsurface aquifers.

This implies the carbon storage in the underground reservoirs of the Earth may be more complex than originally thought.

Pools of CO2 are found in both natural geological accumulations (underground reservoirs) and engineered saline aquifers.

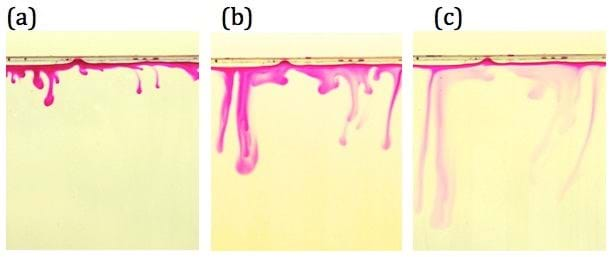

It had been though that once the CO2 dissolved in the formulation water it would become denser and thus convection streams will more efficiently transfer it to depth, but this work suggests that this may not be the case.

Recently published in Nature Communications the study demonstrates that distinct regimes of CO2 transportation may occur in deep saline rock formations, like those in the Earth’s crust.

The paper suggests that the ability of CO2 to be stored in rocks is dependent on geochemical reactions between the dissolved CO2 itself and the porous rock formation.

Dr Silvana Cardoso, reader in fluid mechanics and the environment from the University of Cambridge and Jeanne Andres, who completed her PhD at Cambridge in 2013, suggest that while streaming of CO2 occurs, the chemical interactions in the silicate-rich rocks may hinder this transport drastically and perhaps even stop it altogether.

Silvana suggests that these results should challenge our view on the rates of carbon storage in the subsurface, and that they imply that pooled CO2 may remain in the shallower regions for hundreds to thousands of years, with the deeper regions remaining virtually carbon free.

“For example, our results suggest that for a rock matrix rich in calcium feldspar, the convection streams may be completely shut-off in a short period of only two months after onset of motion.

"After this, the carbon dioxide will be transported to depth by much slower diffusional processes. This finding has important practical implications for storage of carbon dioxide in saline aquifers, enabling informed screening of the most effective sites," said Silvana.

It is excellent to see work like this being completed and I hope that it can go on to help us make better and more efficient decisions over where to place our CCS sites.