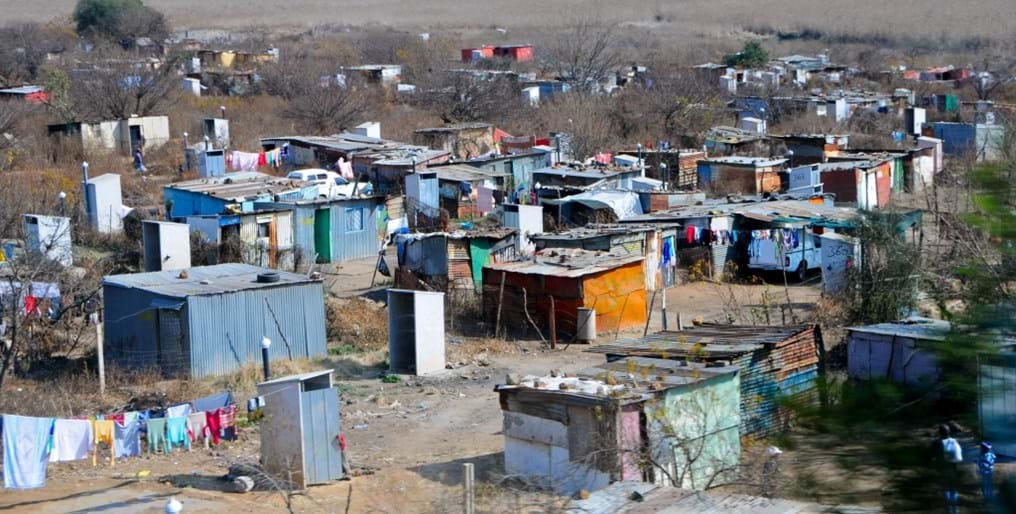

The inequality of health (Day 187)

30th November 2014

Today's blog also starts with a list, but is significantly more sobering than previous stories.

Here's five things about the inequality of health, which should make us all stop and think:

- Children from the poorest 20 per cent of households are nearly twice as likely to die before their fifth birthday as children in the richest 20 per cent.

- Around 95 per cent of TB deaths are in the developing world.

- About 80 per cent of noncommunicable diseases are in low- and middle-income countries.

- In low-income countries, the average life expectancy is 57, while in high-income countries, it is 80.

- Developing countries account for 99 per cent of annual maternal deaths in the world.

The knowledge that money, or the lack of it, is a major root cause of poor health and high mortality is well-known. But what do we do about it?

Economic growth is one answer, but that can take many generations. Another, more immediate answer, is to drive down the cost of healthcare, led by the work of chemical engineers.

Today's blog features the work of chemical engineers at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay (IIT-B), who have developed a special membrane that cuts the cost and time required for dialysis by almost 50 per cent.

Dialysis is the process of artificially removing waste and excess water from the blood in people suffering from chronic kidney failure.

Unfortunately, India has a very high mortality rate for people suffering from kidney failure. However, this may change in the next few years. IIT-B's chemical engineering department has developed a hollow-fiber membrane which is awaiting pre-clinical trials.

The membrane developed by IIT-B is a key component of the filter and removes impurities from the blood during hemodialysis.

The researchers have formulated a special material which improves performance in terms of separation and biocompatibility. It also permits faster treatment, lesser side reactions and could spur novel devices such like portable and wearable dialysers.

In some cases, the current filters can lead to unwanted effects such as compliment activation and inflammation to the patients. IIT researchers claim that the membrane developed by them shows superior biocompatibility.

"Our research could potentially lead to development of a bio-artificial organ that functions as a kidney or liver" says IIT-B chemical engineer Jayesh Bellaire.

According to the Asian Institute of Medical Science few kidney failure patients are able to afford dialysis because of lack of infrastructure and cost constraints.

Dialysis is a recurring cost with filters costing costing 600-1,000 Rupees (£6-10) in India.

To save costs, many patients reuse this filter five or six times, exposing themselves to infections such as Hepatitis B and C.

"Most of these filters are imported and they remain a financial burden to the patients. A filter developed indigenously in India will help decrease the cost and more people will be able to afford it" said Dr Jitendra Kumar from the Asian Institute of Medical Science.

IIT-B hope to commercialise their product within three years, and they already have an indigenous, low-cost pilot plant for production of the membranes.

We wish them every success as they create a more sustainable and affordable healthcare solution for India.