A profession under pressure? (Day 150)

24th October 2014

Welcome to Day 150 of my IChemE presidency.

A thought-provoking report was published yesterday by the Royal Academy of Engineering called The Universe of Engineering - a call to action.

The report is a joint effort by the professional engineering institutions (PEIs), which represent the 450,000 professional engineers in the UK.

On word, in particular, in the report caught my attention - 'adapt'.

Dame Sue Ion DBE, chair of the working group that produced the report, said: “As engineers underpin an increasing number of different parts of the economy and society, the engineering community and professional engineering institutions must adapt to represent and support those in both traditional and non-traditional engineering roles.

“The engineering profession now has a critical opportunity to identify and put into place a framework for the new model of engineering, with its increasing inter-disciplinarity and pervasive reach.”

The report says: "UK is facing an unprecedented skills crisis... the UK will need over a million new engineers and technicians by 2020 and EngineeringUK research shows this will require a doubling of the number of annual engineering graduates and apprentices.

"This will require a step change in the effort to attract young people into the engineering and it must start with coordinated, inspiring messaging to the public that truly captures the real nature and breadth of engineering in the 21st century."

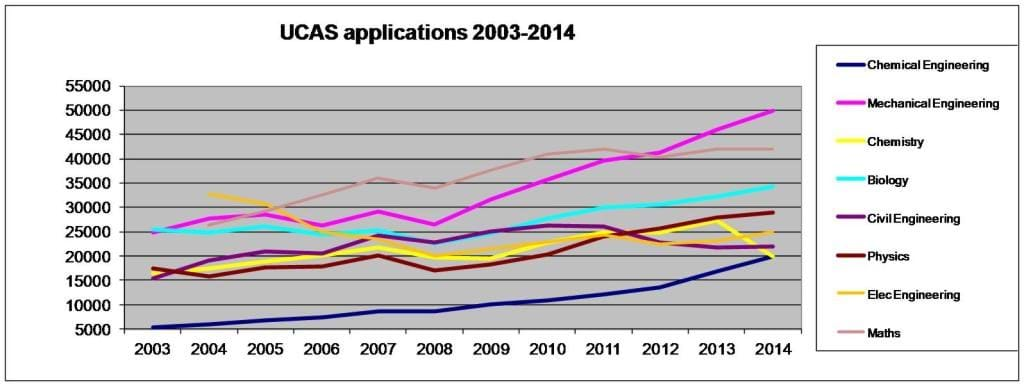

These are huge numbers and a daunting challenge. The good news is that more and more people are being attracted to apply for engineering and science-based courses at UK Universities. The bad news is that this still probably isn't enough.

The report suggested eight key recommendations to bridge the gap from where we are now, to where we need to be in 2020 - just five years away:

- develop a dynamic set of images and messaging to inspire and excite;

- cast the net wider in terms to bring people into the profession and develop them at all levels, from apprentice to chartered;

- work with government to develop employment statistics and measures of economic activity that reflect more properly the role of engineering;

- work with government to drive improvement in careers guidance;

- improve opportunities in engineering for women and those from underrepresented social and ethnic groups;

- professional engineering institutions (PEIs) should prepare for the impending increases in apprenticeships and vocational training routes into engineering by providing opportunities for registration and progression;

- PEIs should work with the FE and HE sectors to ensure that industrially experienced engineers provide contextualised learning;

- government departments should recognise the value that can be gained from greater use of the independent engineering advice from the professional engineering community. As a major employer, government should also lead by example in ensuring the engineers it employs are registered.

I think most people in the profession would support these sensible recommendations. I would also like to add another issue - capacity.

To avoid skill shortages we need more capacity to train engineers, especially chemical engineers. It is always a major step for a University to take on the risk of a new course, but there was some good news this week with the University of Huddersfield launching a chemical engineering course.

Programme leader Grant Campbell, formally of the University of Manchester, says that for several decades Huddersfield has taught chemical engineering as part of its chemistry offerings. But with demand for chemical engineering degrees growing across the country, the university decided it would make sense to launch a full course.

Grant says: “The chemical engineering programme is building on long-standing strengths in chemistry and pharmaceutics, which are attractive to students and employers.”

“Some of our students have been employed in chemical industries in the north-east and are now taking the opportunity to pursue a formal chemical engineering degree.”

Campbell adds that he hopes to achieve a steady intake of 60-80 students within a few years, and to get Huddersfield’s programmes accredited once its first students have graduated. He also plans to develop the university’s research activities, based on the strengths of newly recruited researchers.

I echo the thoughts and sentiments of IChemE vice president for qualifications, Colin Webb, who is “delighted” that Huddersfield is helping to increase the provision of chemical engineering education in the UK.

This is excellent and timely news. However, the message is loud and clear from the Royal Academy of Engineering - our profession needs to become more diverse and portray itself as the modern, exciting, innovative and rewarding profession we all know it is.

If we don't do this, we may become a profession unable to meet the needs of industry and the UK economy. Now that would be pressure.