An antibiotic-free fight against sepsis (Day 59)

25th July 2014

Sepsis, sometimes called 'blood poisoning', is a fairly common whole body infection that can lead to multiple organ failure and death. It is caused by bacteria, fungi or protozoa such as Malaria.

Hospitalised patients recovering from operations, and people with weak or compromised immune systems are particularly at risk, although it can develop from something as simple as a dirty wound.

Even developed countries struggle to manage the infection. In the US, each year, 750,000 cases of sepsis are recorded. In Germany, sepsis claims 60,000 lives annually and is the third most common cause of death.

Even antibiotics struggle to manage the infection, with mortality rates at between 28-50 per cent. It's a major global health problem recognised each year by World Sepsis Day on 13 September 2014.

However, there is some good news.

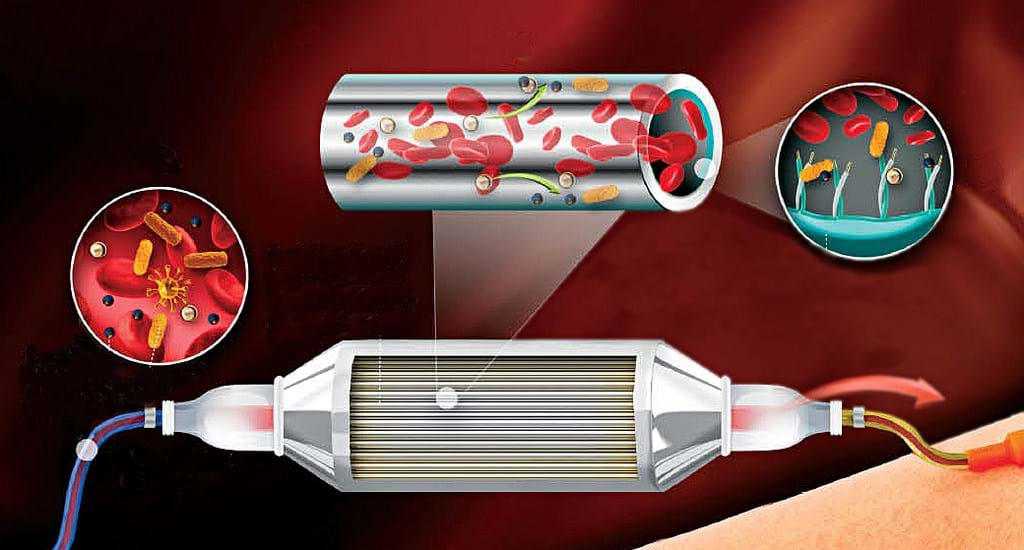

Chemical engineers at Oregon State University (OSU) in the US have used microchannel technology and special coatings to create a small device through which blood could be processed, removing the problematic endotoxins and preventing sepsis.

The device moves blood through a very small processor, about the size of a coffee mug, and literally grabs the endotoxins before removing them.

The blood is pumped through thousands of microchannels that are coated with what researchers call “pendant polymer brushes,” with repeating chains of carbon and oxygen atoms anchored on the surface.

This helps prevent blood proteins and cells from sticking or coagulating. On the end of each pendant chain is a peptide – or bioactive agent – that binds tightly to the endotoxin and removes it from the blood, which then goes directly back to the patient.

Karl Schilke, OSU's Callahan Faculty Scholar in Chemical Engineering, says: “This doesn’t just kill bacteria and leave floating fragments behind, it sticks to and removes the circulating bacteria and endotoxin particles that might help trigger a sepsis reaction.

“We hope to emboss the device out of low-cost polymers, so it should be inexpensive enough that it can be used once and then discarded.

“The low cost would also allow treatment even before sepsis is apparent. Anytime there’s a concern about sepsis developing – due to an injury, a wound, an operation, or an infection – you could get ahead of the problem.”

OSU have just been just awarded $200,000 from the National Science Foundation to continue their work.

In a period when there is increasing concern about the growing resistance to antibiotics, this is a welcome development in the battle against infection.